Some observations on the requirements for scale models to fly at scale speed

Slightly intrigued by the opinion in model aeroplane litterature, that scale models more often than not are regarded as “difficult”, I began to search for the troubeling aerodynamic rules connected with having small scale models fly at scale speed. Vague hints in the direction of wing loading figures was all I ever managed to locate during a somewhat concentrated effort, whereas the more specific hard-core information I was out to hunt always seemed to evade any book or article I came across. Finally, curiosity made me sharpen my pencil and figure it out for myself. The results do not pretend to be mindblowing news by any measure (some of them are indeed trivial), and no doubt they have all been presented elsewhere by numerous other persons many times in the past. Of the double-sided problem that I find it to be, namely one of weight and one of aerofoil behaviour in the low Reynolds regime, the weight part is relatively simple and may easily be done with, while the second part is substantially more elusive, in worst cases uncontrollable to the point of overturning all efforts towards very small scale model feasibility.

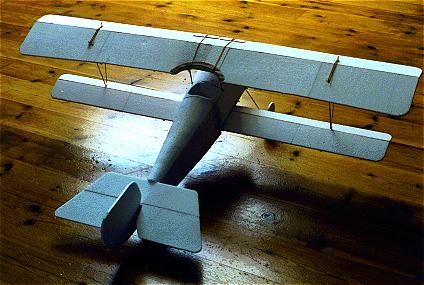

Experimental Nieuport-17 built to 1/8 scale from white foam sheets of 5 mm thickness. Wingspan 1 m, weight 135 gram (including 20 gram noseballast). Glides at about 3 m/s.

What everyone knows

Time is fixed. One second is one second, come what may.

Distance is 1-Dimensional, hence velocity is also 1D.

Area is 2D.

Volume is 3D, hence mass is also 3D.

Let $$r$$ be the scale (reduction) factor.

For $$r = 12$$, the model is in scale $$1 \div 12$$

Scaling down, the distance shrinks to $$1 \div r$$, the area shrinks to $$1 \div r^2$$, the volume to $$1 \div r^3$$

When we say, for instance, that a model is in scale $$1 \div 12$$, we refer to the 1D properties (distances). From this fact follows that areas must be $$1 \div (12\times12)$$ and volumes must be $$1 \div (12\times12\times12)$$.

What scalemodelers should know

In order not to bore readers more than necessary, the outcome is presented first, the details and comments later for those who might want a closer look. In everything that follows, the subscript 1 stands for some property of the full size aeroplane, while subscript 2 is reserved for the model.

Remark 1 Concerning weight ( mass, to be correct ), there seems to be no principle which in itself prevents very small models from flying at scale speed. The limitation lies alone with our own abilities of very light construction.

Remark 2 Concerning aerofoil performance at very small Reynolds numbers, odd problems may considerably jeopardize very small scale model feasibility. More efficient non-scale wing profiles might be brought into play, only somewhere there will be an insurmountable barrier to the gain that can be attained this way.

Rule 1

A property, often referred to when comparing aircraft, is the wing loading, z, i.e. total mass divided by wingarea. If we scale down, the wingarea diminishes by the square, whereas the volume, and hence mass, diminishes by the cube, that is, the mass shrinks faster than the area, which in turn means that the model always will have less wingloading than the full size plane. This principle of “lost” wingloading is also known - at least in the model aeroplane folklore - as the “square-cube” law. Quite clearly it will only be valid on the condition that the materials used for the model are of roughly the same density as those for the full size machine, and that the two structures are fairly similar.

Let $$w_1$$ and $$w_2$$ be the masses of the prototype and model respectively, and let $$S_1$$ and $$S_2$$ be the areas of the wing surfaces:

Rule 2

Of special interest for aeroplanes is the Lift Equation: $$L = C_L \times q \times S$$

The Lift Equation in full:

Or, upon rearrangement:

Rearranging for velocity squared:

Comparing model velocity to full size velocity:

Substituting $$z_2$$ by Rule 1 leads to:

Of likely interest may also be to compare the original velocity, $$v_2$$, with the resultant velocity, $$v_3$$, in case the model mass ( and hence wingloading ) is changed:

Calculated Example Spitfire 1/12 scale

Full Size Aircraft:

Model: $$r = 12$$, leads to:

It is interesting to note that the velocity 16.7 m/s is not to scale, which has to do with velocity appearing as squared in the lift equation. If we insist on flying our model at true scale speed, obviously one or more of the other parameters in the lift equation will have to be changed in order to compensate for the squared velocity. As it turns out, only $$C_L$$ and w are free for manipulation, of which the $$C_L$$ is not easily adjustable, so clearly the candidate for tampering with must be w, the model mass. But before solving the problem, let’s take a look at an expert’s opinion:

In his book “Rubber powered airplane models”, Don Ross gives some valuable numbers for the optimal wingloadings of small flying models. The unit chosen, $$gram/in^2$$, is an unusual example of bad taste, but fortunately the conversion is easy enough.

Ross says that for a small duration model ( e.g. Peanut scale, 13" wingspan ( 33 cm )), the best wingloading should be about 0.33 $$gram/in^2$$, and for a medium size plane ( about 30" ( 76 cm )), it should be somewhere around 0.5 $$gram/in^2$$. Converting these two figures to more familiar units:

These values, to be sure, are for duration models. From other sources I have found that R/C people are not particularly unhappy about quite large wingloadings, as long as they do not exceed $$20 oz/ft^2 = 6.1 kg/m^2$$ (a crude average extract from several Newsgroup posts). So our Spitfire of $$11 kg/m^2$$ apparently has a severe weight problem for rubber duration and R/C alike, besides the fact that it’s totally out of range of true scale speed. Of course, the 1.74 kg is a worst case example, and we would no doubt have little difficulty in building the model a lot lighter than that, only we still don’t know just exactly how light it needs to be. What I will show you in a moment, is that we can actually develop a simple rule to determine the mass of the model so that it should fly at scale velocity, everything else being equal (which may not be the case). I shall give you the details shortly, but for now I can reveal that should our model be able to fly at 4.8 m/s, it would require that the mass be 0.145 kg, dramatically different from the 1.74 kg, and, as it were, exactly 1/12 of 1.74. The resultant wingloading would be $$0.145 \div 0.156 = 0.93 kg/m^2$$. Now take a second look at the value Ross gives for medium sized models. We are quite close.

Rule 3

Rearranging the lift equation for mass:

Under the somewhat bold assumption that CL remains constant for the full size aeroplane and the model alike, we may write:

Comparing the two:

Inserting these expressions for v2 and S2 we get:

( This is the piece of information I originally went out to find ).

Table of scale effect, resulting from Rule 3. Original mass = 3000 kg, original vel. = 58 m/s

| Scale | Mass (gram) | Wingloading (kg/m2) | Scale speed (m/s) | Re (description below) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/4 | 11719 | 8.33 | 14.5 | 555000 |

| 1/6 | 2315 | 3.70 | 9.7 | 247000 |

| 1/8 | 732 | 2.08 | 7.3 | 139000 |

| 1/10 | 300 | 1.33 | 5.8 | 89000 |

| 1/12 | 145 | 0.93 | 4.8 | 62000 |

| 1/16 | 46 | 0.52 | 3.6 | 35000 |

| 1/24 | 9 | 0.23 | 2.4 | 15000 |

| 1/32 | 3 | 0.13 | 1.8 | 8700 |

| 1/48 | 0.6 | 0.058 | 1.2 | 3800 |

| 1/64 | 0.2 | 0.033 | 0.9 | 2100 |

| 1/72 | 0.1 | 0.026 | 0.8 | 1700 |

With regards to mass alone it appears that in principle there is no problem with scaling down and remain flying at scale speed. The practical construction of such extremely lightweight devices as required in the small scale regime may however not always come easy. As to our imaginary 1/12 scale Spitfire model above, we could easily find ourselves in a situation where we do not have sufficiently lightweight components at hand to get away with anything more than a crude free-flight version. The finest successful example I have heard of so far (Walter Scholl, E-zone sep. 1997) is a Blériot XI, 1/10 scale model of 115 gram mass, electric engine and micro R/C included, and flying at scale speed 2 m/s. The wingloading is $$0.46 kg/m^2$$, even less than Ross’ smallest figure.

Alarmingly primitive Bf 109 F prototype in mixed foam/balsa, built to 1/12 scale.

Although the artistic appearance of this my first foam job ever is nothing to be proud of, the aerodynamic properties are not bad at all. Wingspan 83 cm, Clark Y-ish aerofoil.

Total weight 128 gram (including 34 gram nose ballast).

Glides at 4.5 m/s. Rate of descent is about 0.75 m/s.

Rule 4

Reynolds number ( Re )

A quite different matter which has to be faced in the process of scaling down, is the aerodynamic behaviour of wingprofiles (aerofoils) operated at small dimensions and/or velocities, as would be required for small models.

To begin with the Reynolds number:

Viscosity, $$\mu$$, may be expressed in $$Pascal \times second$$, $$Pa \times s = kg \div (m \times s)$$

For comparison, 55 times more viscous:

Reynolds number $$(Re) = c \times v \times d \div \mu$$

( $$c$$, $$v$$ and $$d$$ as defined earlier in details of Rule 2; $$d \div \mu$$ has the dimension $$second \div m^2$$ )

With $$c$$ in meter, and $$v$$ in meter/second, $$Re \approx 68000 \times c \times v$$

With $$c$$ in feet, and $$v$$ in feet/second, $$Re \approx 6410 \times c \times v$$

Full size aeroplanes have Re in the million class, whereas indoor models may come as low as 10000 (microfilm). Tables or plots of lift and drag coefficients as a function of angle of attack (AoA, or alpha) and different Reynolds numbers are valuable when comparing aerofoils, as well as an indication of which dimensions and/or velocities better to be avoided for a specific wing profile. Data to this effect are most often obtained from windtunnel tests, but also theoretical tools are capable of calculating fair predictions, as long as we make sure to stay above Re 100000. One such tool by Martin Hepperle is given in a link at the end of this webpage. The book by Martin Simons, also listed below, devotes several chapters to the presentation and discussion of aerofoil and windtunnel data.

In the notes to Rule 3 it was mentioned in passing that lift coefficients for the full size plane and the model might not be quite the same value. Although it was a prerequisite for developing Rule 3, and may well be close enough to the truth for large models like 1/4 or 1/6 scale, it’s not likely to be an equally safe assumption for smaller models, say 1/10 and less. The problem here is the almost total absence of linearity between the lifting capacity of two aerofoils of equal proportions but different size. One cannot safely assume, without windtunnel evidence or practical field experiments, that a downscaled version of some specific wing profile will have any relationship with the full size version in terms of efficiency; in fact an extensive amount of published data strongly indicates that the smaller of the two will show a markedly inferior performance, and that the trouble usually aggravates as we move towards the very low Reynolds regime. What happens here is that inertial forces to some extent loose their grip in a struggle against viscous forces. Let me give you a taste of what’s to be expected, by a few examples, which, with the exception of EJ 85, are all drawn from Simons, more or less at random:

| Re | cl |

|---|---|

| 168000 | 0.94 |

| 126000 | 0.93 |

| 105000 | 0.90 |

| 84000 | 0.87 |

| 63000 | 0.50 |

| 42000 | 0.44 |

| 21000 | 0.42 |

| Re | cl |

|---|---|

| 3000000 | 0.75 |

| 250000 | 0.70 |

| 75000 | 0.70 |

| 60000 | 0.50 |

| 45000 | 0.38 |

| 30000 | 0.31 |

| 20000 | 0.27 |

| Re | cl |

|---|---|

| 170000 | 0.88 |

| 100000 | 0.88 |

| 75000 | 0.83 + |

| 75000 | 0.65 + |

| 63000 | 0.55 |

| 42000 | 0.47 |

| 21000 | 0.40 |

| Re | cl |

|---|---|

| 189000 | 1.16 |

| 84000 | 0.86 |

| 63000 | 0.65 |

| 42000 | 0.59 |

| 21000 | 0.76 |

| 14000 | 0.90 |

| Re | cl |

|---|---|

| 120000 | 0.71 |

| 60000 | 0.71 |

| 30000 | 0.71 |

| 20000 | 0.65 |

| Re | cl |

|---|---|

| 83000 | 0.95 |

| 60000 | 0.95 |

| 40000 | 0.93 |

| 20000 | 0.70 |

A few notes

Göttingen 801: Suspicious behaviour around Re 75000 ( marked with + ), as part of a so-called hysteresis loop, with the effect that in a certain Re range, and specific AoA, the profile gives a better performance in going from higher to lower speed than in going from lower to higher. This unpleasant behaviour is shown by many profiles, including N60 and Gö 417b (at higher AoA than 3°), whereas this is not the case with NACA 4412, HK 8556 [T] and EJ 85. See Simons for details if you are interested. Göttingen 417b, curved plate: Surprises at Re 21000 and 14000, although accompanied by large increases in profile drag (not shown). HK 8556 [T] Turbulator, and EJ 85: These profiles seem to be extraordinarily forgiving at all velocities and/or dimensions. EJ 85 is a Jedelsky profile.

As seen in the previous few tables, it’s evident that the highest lift coefficients coincide with the highest Reynolds numbers, and also that above a certain Re the gain in lift capacity with a further increase in Re is extremely limited, if any at all. In the low end of the Re scale, for most profiles the lift coefficients are more widely scattered with changes in Re. Apart from that, any broad generalisation is difficult to make because of exceptions and surprises, thus rendering predictions a little hazy. For real flying devices, matters are slightly more complicated, as most often we need to know the amount of power required for flight and/or the distance covered in a glide from a certain height. Various drag components must be lumped together and compared with the lift coefficients, in order to make a realistic estimate of the rate of descent and hence the usefulness of some particular wing in connection with the rest of the aeroplane. All this, however, is so much better described in textbooks like the ones by Simons and Stinton.

At present, it is believed that for very small models, the best job will be done by a thin, highly cambered wing profile, even such seemingly simple ones as the broken plate variation of a Jedelsky profile (see Don Ross). This again indicates that perfect scale appearence - for all but pre 1920 aeroplanes - may have to be sacrificed to some extent. In Aeromodeller, sep / oct 1997, vol 62, No 742 and 743, two articles “Foam at last!” by David Deadman, describe the construction of lightweight and extraordinarily realistic peanut scale models. I have been informed that one of the author’s planes, a Lavochkin La-7, scale approx 1/30 and weight 13 gram, flies at about 4.8 m/s, corresponding to 80 % of scale maximum speed. According to Rule 3 above, the “ideal” weight should rather have been close to 4 gram, but the La-7 model features a curved plate wing with a lift capacity large enough to compensate for the extra weight. Had the original wing profile been retained for strict scale appearence, the resulting model speed would have been in the vicinity of 9 m/s. Mr. Deadman’s La-7 perfectly illustrates the tradeoff between weight and lift capacity that has to be accepted when rather small scale models are to fly at scale speed.

From the observations accumulated here, I should think that from about scale 1/8 and down, weight will be the primary problem to solve, while from approx. 1/10 and downwards, aerodynamic trouble will begin to mix heavily in and pile up at a dramatic rate as we move towards smaller dimensions. Lower lift coefficients translate into larger velocities (by the lift equation) and will have to be either compensated for by a more or less drastic change of wing profile (as far as it goes), or counterbalanced by an even further weight reduction in a model which may already be stripped to the limit.

Literature

Martin Simons: Model aircraft aerodynamics. (1994)

Darrol Stinton: The design of the aeroplane. (1983)

Don Ross: Rubber powered model airplanes (1988)

Links

Walter Scholl (E-Zone article): http://ezonemag.com/articles/wiw/091997/wiw0997.htm

Martin Hepperle: http://beadec1.ea.bs.dlr.de/Airfoils/calcfoil.htm

Bob Boucher. A different view of scale flight, taking scale maneuvers into account: http://www.astroflight.com/astroflight/scalespeed.html